“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew.” Abraham Lincoln[1]

Technology transfer does not have a globally accepted definition, in its broadest form it is the sharing or transfer of knowledge or technology from one entity to another. To define technology transfer is a futile activity according to Bozeman (2000). Technology transfer is situational, technology transfer is non-specific, it is fluid and in that is adaptable and applicable across boundaries, organisations, and technology, in this I see huge opportunity for our research.

This challenge of understanding business-to-business (B2B) technology transfer is the first question of our ‘Technology Transfer Research Programme’ with Cranfield University and QinetiQ. This article raises the questions and thoughts that have arisen from our early synthesis of academic knowledge around this question.

The research has highlighted three constant characteristics of technology transfer so far:

- Technology Transfer is active; the literature often uses active adjectives when describing technology transfer, with over 55% of literature using the term ‘process’. This implies technology transfer is an activity – a series of decisions and actions to enable the commercialisation of know-how and technology using technology transfer. I would argue that as an activity technology transfer is more than a single mechanism of deployment, it is not an isolated activity, nor is it a purely reactive one.

- Human activity is inseparable from the technology transfer process, 82% of literature reviewed to date directly, or indirectly, accounts for the human element. This is seen in the large body of research into the role of agents, culture, and learning and development in technology transfer.

- Knowledge transfer is inherent to technology transfer. Whereas knowledge can be transferred without technology, technology can’t be transferred without the associated knowledge (Sahal, 1982) – re-iterating the other constant characteristic of the inseparable human element. It can also go beyond ‘tangible’ knowledge, the inherent knowledge within individuals, the background theories and the broader vision of the original programmes are all integral to the activity of technology transfer in our experience at MULTIPLY. Technology transfer is not a software programme that can run a script and execute a solution. In the experience we’ve had at MULTIPLY, the technology transfer process warrants a mixture of statistical analysis and human intuition and knowledge within a framework, to improve confidence quickly and make informed decisions on what, where, with whom and how to deliver.

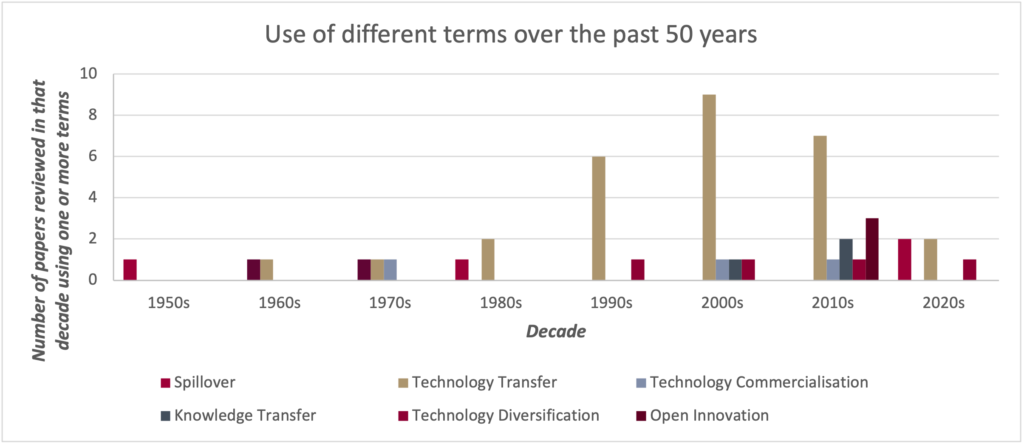

Beyond these core characteristics, the literature appears to fragment, and we see technology transfer becoming situationally dependent. The variations in terminology and characterisation of technology transfer are often based on actors, technology type, sectors, flow of transfer and academic disciplines. This is reflected in the various terms used to describe a particular technology transfer situation.

Identifying which terms for technology transfer to pay attention to isn’t a purely tautological issue, where different words and phrases are used to express the same idea. Each expression is situational, which can inform or be excluded from a characterisation of B2B technology transfer; so far, we’ve identified six main terms that could contribute to a characterisation of B2B technology transfer:

- Horizontal technology transfer: the transfer of technology to be used in another place (Resiman, 2005)

- Spillover: often seen as a responsive ‘by-product’ of an existing activity (Nelson, 1959)

- Knowledge Transfer: Where one unit is affected by the experience of another (Argote and Ingram, 2000)

- Technology Commercialisation: Bringing the contractual, commercial nature of technology transfer into the characterisation (Vaitsos, 1971)

- Technology Diversification: Focusses on the technological competence of an organisation (Granstrand & Oskarsson, 1994)

- Outbound Open Innovation: Clearly defines the flow direction, necessary for the characterisation of B2B technology transfer (Chesbrough, 2006)

At MULTIPLY we believe there are three core requirements to empower organisations and individuals to pro-actively do B2B technology transfer:

- Understand: A common understanding of what B2B technology transfer is (if that will ultimately be the correct term to use). This provides a uniform language and clarity for industry, academia, and government.

- Access: Providing access to tools, models and networks is key to empowering and enabling individuals and organisations to embark on B2B technology transfer initiatives.

- Support: existing government funded activities like the KTN, and Innovate Edge are steps toward this. However, there is a long way to go, through policies, funding considerations and support mechanisms specifically to enable organisations to do B2B technology transfer not just access networks.

Our limits are defined by constructs, often not of our own making. In conversation I noted most people are familiar with the term technology transfer in context of university or research institute to industry activity. In our work at MULTIPLY, focusing on B2B technology transfer, we argue that technology transfer does not have to just come from a research unit. Due to the lack of clarity and single terms to explain the outbound flow of technology from one organisation to another, as we’ve seen in the literature so far, it is unsurprising that the understanding of B2B technology transfer is limited to this way of thinking. I wonder if this is why so few advanced engineering companies are pro-actively transferring technology as we saw in our 2020 study?

It is these perceptions and biases that, in part, drive the research programme to enable us to look at the world anew.

Subscribe here to be kept up to date with our research and other MULTIPLY activity.

References

- Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1006/OBHD.2000.2893

- Bozeman, B. (2000). Technology transfer and public policy: a review of research and theory. In Research Policy (Vol. 29). www.elsevier.nlrlocatereconbase

- Chesbrough, H. (2006). Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm: Oxford University Press, 1–12.

- Granstrand, O., & Oskarsson, C. (1994). Technology Diversification in “MUL-TECH” Corporations. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ENGINEERING MANAGEMENT, 41(4). https://doi.org/10.1109/17.36455

- Nelson, R. R. (1959). The simple economics of basic scientific research. Journal of Political Economy, 67(3), 297–306.

- Reisman, A. (2005). Transfer of technologies: a cross-disciplinary taxonomy. Omega, 33, 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2004.04.004

- Sahal, D. (1982). The form of technology. In: Sahal, D. Ed. , The Transfer and Utilization of Technical Knowledge. Lexington Publishing.

- Vaitsos, C. V. (1971). The process of commercialization of technology in the Andean Pact: a synthesis. s. Washington, DC: Organization of American State.

[1] Abraham Lincoln Quotes. (n.d.). BrainyQuote.com. Retrieved November 22, 2022, from BrainyQuote.com Web site: https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/abraham_lincoln_121071